Anna-Sophie Springer & Etienne Turpin, eds.

The Word for World is Still Forest

intercalations: paginated exhibition

intercalations 4 ... creates a space for the reader-as-exhibition-viewer to consider how forests may be seen not only for their trees, but also how they can enable experiences of elegance, affirmation, and creation for a multitude of creatures; in response to their violent destruction, which characterizes the Anthropocene, these pages traverse various woodlands by way of their semiotic, socio-political, historical, and epistemic incitements in order to reveal how practices of care, concern, and attention also enable humans to inhabit and flourish in this world as forest.

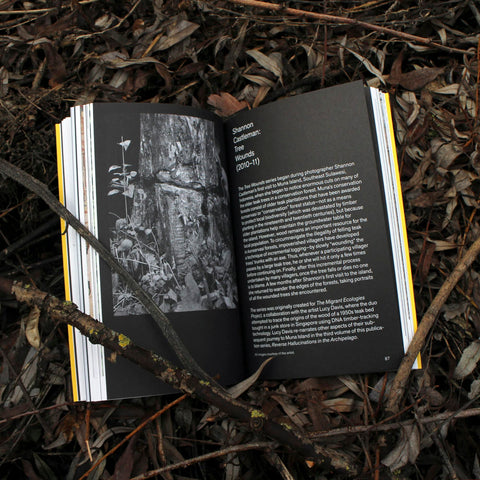

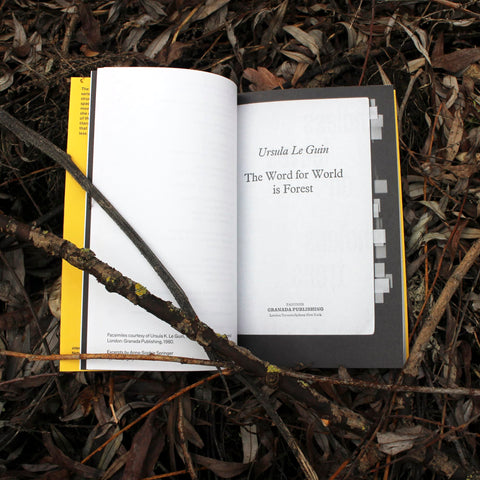

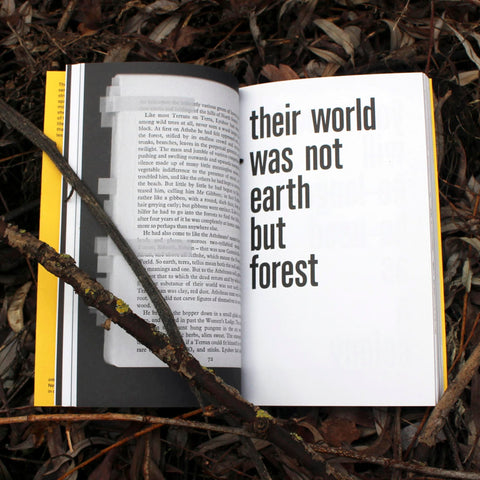

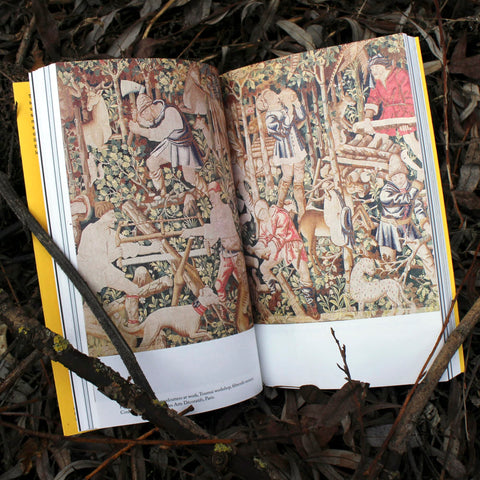

The Word for World is Still Forest is an homage to the forest as a turbulent, interconnected, multinature. It moves from concepts of the forest as a thinking organism to the linear monocultural plantations that now threaten the life of global forests. The volume opens with a series of facsimile pages from Ursula K. Le Guin’s eponymous novella The Word for World is Forest from 1972, for which the editors scanned their personal, marked-up copy for excerpts that now read like poetic, urgent pledges. In a provocative essay, the artist Pedro Neves Marques shares his understanding of the particularity of Amerindian images of naturecultures. Architectural historian and curator Dan Handel then presents an excerpted exhibition on “wood” as a vital element of forest mythology and the driver of industrial resource management. Alongside data visualizations by arborealist Kevin Beiler, Canadian forest ecologist Suzanne Simard explains how trees are connected by the “wood wide web” and describes how the Mother Trees of British Columbia distribute nutrients through an underground mycorrhizal fungi network. Media designer and data curator Yanni A. Loukissas adds a series of reflections on botanical data from Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. In her intriguing photo series, Shannon Lee Castleman visualizes illegal logging, incremental harvesting practices, and ghostly hauntings in the diminished tropical forests of Indonesia. Nonuya elder and shaman Abel Rodríguez also shares Indigenous worldviews and spirituality by relaying an oral narrative of the Ancestral Tree of Plenty in a piece transcribed and translated in collaboration with Carlos Rodríguez and Catalina Vargas from the Tropen Bos International Colombia forest conservation group. Abel’s deep knowledge and understanding of the forest also emanates from the beautiful drawings of medicinal plants and wet and dry seasons in the Amazon. Brazilian architect and activist Paulo Tavares continues to address human rights violations and Indigenous struggle in Amazonia as he highlights the hybrid literacies required by resistance groups in defense of their land against dispossession and epistemicide. In the interview “Leaving the Forest,” anthropologist Eduardo Kohn discusses the meaning of perspectival multinatural semiotics following his time with the Kichua Rina in Ecuador. Finally, the book concludes with two episodes from Berlin, where the book was produced: architect and neighborhood activist Silvan Linden portrays a case study of Berlin’s controversial urban “wild,” and landscape architect and photographer Sandra Bartoli reverently illuminates the little-known history of the oldest trees surviving in the Tiergarten, Berlin’s central park and former royal hunting forest. Throughout the book, artist Katie Holten’s “Tree Alphabet ’’ evokes connections between the book and its arboreal origins.

Made possible by the Schering Stiftung.

The Word for World is Still Forest. Edited by Anna-Sophie Springer & Etienne Turpin. With contributions by Sandra Bartoli, Kevin Beiler, Shannon Castleman, Dan Handel, Katie Holten, Silvan Linden, Yanni A. Loukissas, Eduardo Kohn, Pedro Neves Marques, Abel Rodríguez, Carlos Rodríguez, Suzanne Simard, Anna-Sophie Springer, Paulo Tavares, Etienne Turpin, and Catalina Vargas Tovar. Design in collaboration with Katharina Tauer.

- English

- 232 pages

- 13 x 21 cm cm

- Full color and BW images, richly illustrated

- Softcover, thread-sewn, flaps, foil stamping

- ISBN: 978-3-9818635-0-5

- Institutional partner: The Anthropocene Project

- Co-published with Haus der Kulturen der Welt

Published on 02 May 2017